In the evening, we enjoyed a nice dinner out and lit Shabbat candles in our room. I posted a few pictures on the Facebook site, "Roots in Keidan"--and promptly got a message for Laima Ardaviciene, a Keidainiai high school teacher who invited us to meet her. We made plans to meet by the old synagogues at 10:00 this morning.

**********

Keidan is a special place for my family. I began this journey with a visit to the gravestone of Rabbi Yehudah Tzvi (Judel) Finkelstein in Queens. He spent out of his life in Kovno/Slabodka, but he was born here in Keidan. Here's how his son, Rabbi Shimon Finkelstein tells the story:

My father was descended from a long line of rabbinic scholars who had lived in Keidan, a town noted in our district for rabbinic learning.I would have remained in complete ignorance of the distinction of his ancestry had I not early in life met a cousin, the daughter of my famous aunt, Chaya Etta of Kovno. My aunt was one of the few Jewish women of her country and generation who had broken through the conventions which barred her sex from public life and had graduated as a nurse from a St. Petersburg school. She had received a medal from the Tsar for excellence in her studies, and in my time was known everywhere in Kovno not only for her eminence in her profession, but also for her wide influence in the community, where she was credited with having been the decisive factor in the selection of various rabbis. Her daughter, who she reared in her own profession and who also attained unusual distinction, was my informant regarding family history. Despite my father's reticence about his forebears, except when he quoted "their Torah," he was aware, as I now understand, of his obligation to them and very eager that his sons should measure up to their standards of learning.

My own father, Arnold Fink, always expressed pride in our Keidaner ancestry. Apparently there was good precedent for this. In his memoir, "Worlds Gone By", Dr. Chaim Yakov Epstein notes: "Keidan was not just another Lithuanian town. It was a city with a noble lineage. Proud was the Jew who, when asked, "Where do you hail from?" could stand up tall and respond, "Ich bin Keidaner--I am a Keidaner."

The city boomed in the 17th century, under the patronage of the ruling Radvila family. Unlike most Lithuanians, in this very Catholic country, they were Calvinists, and big believers in religious tolerance. Keidan attracted Germans and Scots--and Jews. The Jewish community here were merchants and brewers and weavers--and also farmers, who cultivated fruits and vegetables and sugar beets. And Keidan's cucumbers, grown by Jewish farmers, were famous throughout Lithuania--and beyond.

It was also a place of deep Jewish learning. David Katzenellenbogen was a famous rabbi here. In 1727, a six year old boy arrived in Keidan from Vilna. His natural talent stunned the rabbis of Keidan, who saw his potential and educated the lad. He would become Rabbi Eliyahu--the Vilna Gaon, one of the greatest Jewish scholars who ever lived. His wife, Channa, was also a Keidaner.

Over the years, this town raised many eminent Jews--religious and secular, Zionists and Talmudists and Bundists and communists and more. Among them were the Hebrew writer Moshe-Leib Lilienblum, a Hebrew writer and poet and leading light in the awakenings of Zionism.

But there was also the stuff of daily life, as described by Boruch Cassel and Chaim Epstein in their memoirs of life in Keidan:

A Saturday night in Tammuz (June/July). After a hot day, the evening has called things off a little, and with the new moon in a clear skyline, the whole city is outdoors. The old bridge is packed with strollers, mostly young people. Girls go with girls, and boys with boys. They walk in pairs, in groups of three or four or more in a row, usually of the same age. The line of boys follows after a line of girls, making jokes at their expense, but the girls give as good as they get, laughing and throwing wisecracks of their own back in the boys direction.

. . . It was was not a long bridge and could be crossed, back and forth, many times, thus giving young men and women many chances to meet.

Who knows? Perhaps my great-great grandparents, Yehuda and Soreh, met on this bridge--which stood in exactly the same place over the Nevezis River where Rosa and I passed into town yesterday.

**********

We met Laima in the old marketplace, outside the two old synagogues, one for the summer and one for the winter. One is now an art school. The other is a museum and cultural center. Both are beautiful.

There is a large Holocaust memorial outside, which contains 2076 bullet shell casings, one for each victim killed in the fields outside of town on August 28, 1941. There are also many large stones. I added a small stone of my own, one of many that I picked up from the bank of the Boise River by the Idaho Anne Frank Human Rights Memorial.

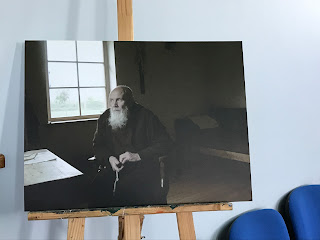

Then Laima led us into the former synagogue that is now a cultural center. Downstairs is an exhibit of art, dedicated the life of an aging local monk who risked his life to save local Jews during the Shoah.

Next, Laima led us through the streets of the city, pointing out buildings that had once been Jewish homes and workplaces--the old drug store, a house with a sukkah attached, merchants' stores. I got teary, thinking of my family living here. We always see pictures of old shtetls in black and white. But life was lived in full color.

When we arrived back at the bank of the Nevezis River, upon which Rosa and I entered the city, we saw a sign for C. Miloso Street. It is named for the Nobel prize winning author, Czeslaw Milosz, who was born near here and who loved Keidan and the Nevezis, which he fictionalized as the Issa River Valley.

In that book, he writes: The Issa Valley has the distinction of being inhabited by an unusually large number of devils. It may be that the hollow willows, mills, and thickets lining the riverbanks provide a convenient cover for those creatures who reveal themselves only when it suits them. . . And how is one to tell them apart, those creatures coinciding with the advent of Christianity from those native inhabitants of bygone days, like the forest witch who switches children in their cradles, or the little people who stray all night from their places under the roots of the elderberry bushes? Are the devils and those other creatures joined in a pact, or do they simply exist side by side like the jay, the sparrow, and the crow? And where is that realm where both species would take refuge when the earth was plowed up by the tracks of tanks; when those who were about to be executed dug their own shallow graves by the river; and when, in blood and tears, Industrialization rose up, surrounded by the halo of History?

To honor Milosz--who bore witness to so much that happened on these banks--the city put up a giant sculpted chair, looking out over the Nevezis. It invites us to sit in Milosz's place, to see the beauty and the horror, to listen and learn.

**********

I mentioned the Radvila family, and their patronage of this city. Outside the town hall, their is a statute in their honor--and they are buried in the Reformation Protestant church, which Laima took us through.

Next, we walked a bit out of town to see the Jewish cemetery. Most of the graves here are over a century old--an even older cemetery adjacent is now destroyed. But there are hundreds of headstones in the intact cemetery. The majority are illegible, the engraving worn away by time and weather. We could read a few. Somewhere here, my Finkelstein ancestors are buried. Laima noted: "These are the lucky ones, who got to pass away rather than being murdered in the forest." I left another stone and sang the traditional mourners' prayer, "El Malei Rachamim."

**********

In memory of those whose graves we saw, a poem (in Leonard Wolf's English translation from the Yiddish) by Keidan native Abraham Reisen:

Future Generations

Future generations,

Brothers still to come,

Don't you dare

Be scornful of our songs.

Songs about the weak,

Songs of the exhausted

In a poor generation,

Before the world's decline.

We were all imbued

With the idea of freedom,

Yet sang our songs about it

With voices lowered.

Far from our good fortune

We met at night, in darkness,

And worked at building bridges

In secrecy.

We hid from the foes

Who lay in wait for us,

And this is why our songs

Resonate with grief,

And why our melodies

Have a dismal longing

And a hidden rage

In their warp and woof.

**********

Then came what was, for me, in many ways, the most remarkable--and inspiring--part of the day.

We walked from the cemetery to Laima's school, Atzalyno Gimnazija, where she teaches English to high school seniors. School ended for the students yesterday--but Laima let us in. We were struck, immediately, by the mural at the entrance--a testimony to Keidan's different religious traditions. Like all the art in this school, it was painted by students.

Just a little further down the hall is another school project--a map showing the places where the Soviets exiled so many Lithuanians during the Russian occupation. They were shipped off to Siberia--and did not all return alive. As we remember the Shoah, and honor the Litvak Jewish community murdered by the Nazis and Lithuanian accomplices, it is important to recall that Stalin, too, bears responsibility for the slaughter and suffering of millions, including multitudes of Lithuanians.

The halls are filled with art--they testify to the power of art to tell stories, to bear witness, to inspire and move us.

**********

And then we came to Laima's classroom.

There are flags from Lithuania and Israel, a menorah, and certificate of honor gifted to Laima by the Tolerance Center, the local organization headed by another hero, Rimantas Zirgulis, doing the hard work of preserving history and using the lessons of the past to build a better future, anchored in human rights for all. There is a map of Lithuania, a poster of London, and numerous great books in English and Lithuanian. But the most prominent feature in the classroom is a large, wall-sized mural of Keidan's two synagogues beneath a giant tree, which is made up of over 1700 names--the names of the Jewish families who lived in this city. At the bottom are those famous Yiddish words of pride, "I am a Keidaner."

This brought me to weeping--for what was lost, but, much more, for the heroic effort Laima and her students are making to honor their city's Jewish past. They have looked straight into the worst of tragedy and brought, against all odds, a belated grace note of redemption. No, nothing can overcome the horror of the Shoah, of 2076 Jews shot into ditches. But this teacher and her students give me hope despite that horror. They remind me that the past need not be prologue to the future, that people and communities and nations can change, that the youth really are the promise of a better tomorrow.

And Laima is leading the way. She showed us projects that her classes have taken on in recent years, YouTube videos of their efforts to map Jewish Keidan, to honor the women of the old Jewish community, to celebrate Chanukah, via Skype, with a Jewish day school in Perth, Australia. And much, much more. She is one of the righteous of the nations, doing sacred work. It was a privilege and an inspiration to sit in her classroom.

**********

For the last destination of the day, Laima called a cab and rode with us past the outskirts of town, down a dirt road, to the place in the forest where the massacre took place.

There are no words to describe this.

I will only say that the contrast, between the peaceful forest and fields and flowers, with their bird song and gentle breeze--and the horror of what happened here--is inconceivable. I cannot begin to fathom it.

But the memorial here is right, in every sense, because it bears the names of those who died--affirming the names, the unique humanity of each of those souls who the Nazis and their local accomplices chose to de-humanize and reduce to mere numbers in order to be able to slaughter them.

Thanks to Rimantas Zirgulis, who conceived of this project, and saw it through to the finish. And to Laima, who brings her students here, every year, where they read the names of the Keidaners who died here.

They were not numbers. They were--and will always be--names. Souls. Humans, created in the Divine Image. This marker, in the face of the utter horror of what happened here, asserts this. The students who read the names inscribed here are, in my mind, praying--in the best sense of the word. They are affirming the Divine in the most godless of places.

With Rosa and Laima, again I wept. And sang El Malei Rachamim. And wept.

**********

We returned to town around 4:00. The cab dropped us off back in Old Town, where we had begun, nearly six hours earlier. We hugged and exchanged addresses. I will be in touch with Laima and her students, of this I am certain.

And at day's end, I was not the same person I'd been when the sun rose.

It was a day of awe and learning and tears and despair and inspiration and, in the end, hope.

It was a blessed Shabbat.

Shavua tov. May it be a week of peace.

No comments:

Post a Comment